Amateur naturalist

Patrick is no stranger to bear encounters, as seen with an indirect sighting of a black bear; a recurring visitor coming by for a lick of salt or a back scratch using tree bark. (Courtesy: Patrick Cross)

Story told by Patrick Cross

Growing up in Kahnawà:ke, hunting was in my blood. It was taught to me by my older brothers. Besides hunting rabbits, I would also hunt partridge, ducks, and fishing was good too.

I had a real good connection with nature growing up. I like to call myself an amateur naturalist.

I am part of the bear clan so I wouldn’t hunt a bear. Maybe if someone else offered me a steak from a bear they hunted, I would accept, but besides that I am not interested in hunting or eating it. I would only shoot it if I had to in self-defense.

One time it happened where I was hunting in the winter and I always brought a little folding chair to sit on. I got to the top of a good-sized hill and did some calling to attract the deer. The next thing I know, I see a black shape out there in the snow. I thought it was a moose calf because it had a big body and was digging in the leaves. It was a bear.

I’m sure it didn’t see me and didn’t smell me because of how the wind was blowing. I don’t know if it got spooked by something but all of a sudden he started running towards me.

I got out of my chair and started to yell, I think it had enough sense to know where my voice was coming from and it started walking away from me. As it was walking away, I started breaking some branches and it started running away.

Sometimes I hunt alone and when I shoot a moose, there are some things I learned to do after shooting an animal.

The first step is to give thanks. I carry tobacco and say my prayers. I touch the fur, apologize and be thankful.

The second step I do is to count the points on the palm of the antlers.

The third thing I do is take some pictures.

The last step is figuring out how I’m going to cut this big thing.

I carry some rope with me and when the moose goes down, I look for a nearby tree. The main thing to do is to tie the back legs to the tree and try to get the belly to face upwards, and then I go in with a knife.

When you gut it, your arms are way in there because you have to dig all the way up and cut through the breast bone to get everything out of there.

If I am alone, I would gut it and then cover it up with branches. I would go back to the main road or wherever I can get a good enough signal and call for help to move it because those moose are so heavy.

Even after you get it into pieces, it’s hard.

In Ahkwesáhsne they make these things called “pack baskets,” they are handmade wooden baskets you can carry on your back with straps.

Normally after you cut the moose into pieces, you would carry those pieces out one at a time.

That’s what a lot of the old-timers used to do, carry a moose leg on their back in those pack baskets.

Just the leg itself is still really heavy, and you have to make a few trips.

Sometimes you get lucky and the moose drops closer to a road so you can get a few vehicles in there to transport the moose. But if not, you’re carrying it out on your back.

Just one moose could be enough meat to last me almost two years. And every time I go to eat a part of it, I make sure to give thanks.

KANIEN’KÉHA VERSION

↓

KANIEN’KÉHA VERSION ↓

Iah Teionkkarià:kis Sha'oié:ra Ionteweiénstha

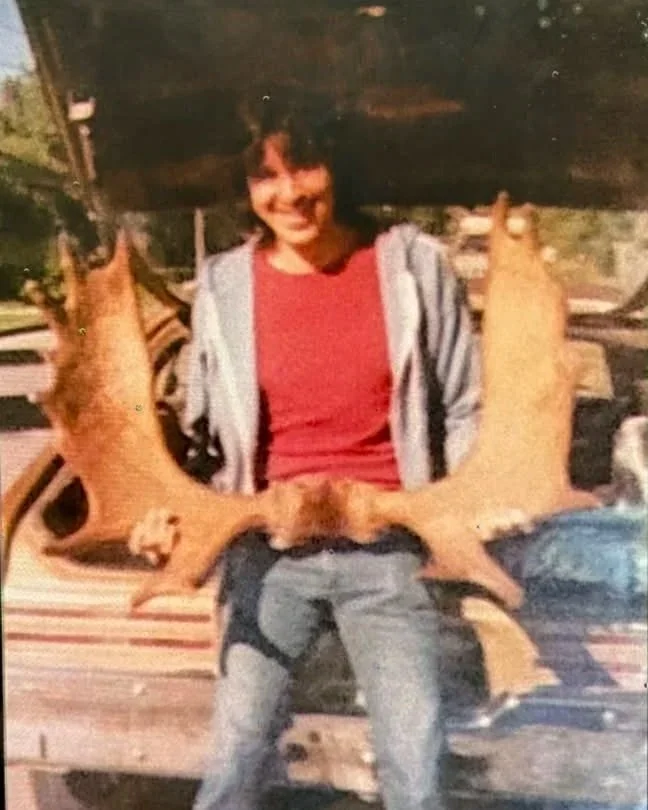

A born hunter all the way back in his youth, Patrick proudly raises a crown of moose antlers, seemingly a 13-pointer, as proof of his hunt. (Courtesy: Patrick Cross)

Patrick Cross ROKÁ:RATON

Kahnawà:ke shiwakatehiahróntie, kwah shiwatáhkhe akenekwénhsakon nakató:rate'. Wa'onkhirihónnien' nì:'i tánon khehtsi'okòn:'a rotisken'rhakéhte'. Tsi tahonhtané:ken kheiató:rats, ne ó:ni ohkwesen'tarì:wase, só:ra enkheiató:rate', tánon ion'wesèn:ne ó:ni nakahrhióhkawine'. Iohní:ron tsi na'teiakenì:neren ne sha'oié:ra shontonkwatehiahróntie'. Wakon'wéskwani' iah teionkkarià:kis sha'oié:ra ionteweiénstha akatatenà:tonhkwe'.

Wakskaré:wake niwaki'tarò:ten' ne ki' tiorì:wa tsi iah tekató:rats nohkwá:ri. Tóka' ónhte ónhkak eniónktatshe ohkwá:ri ohwénhson néne konwatorá:ton', entié:na' ki' thí:ken nek tsi iah ki' othé:nen tetewake'nikonhratihénthos akató:rate' tóka'ni á:keke' thí:ken ó:ni. Nek enkaròn:tate' thí:ken tóka' tenwatonhóntsohwe' aontakatatéhnhe'.

Énska tsi náhe shikató:rats nakohsera'kè:ne tánon tió:konte' entékhawe' ken' niwanitskwahra'tshera:'a teiehsà:kets naionnitskó:tahkwe'. Eh è:neken' ne tó:k niionón:tes wa'kenontohá:ra'ne tánon wa'tkatewennaierónnion' ne oskennón:ton' aontakheia'tatirón:ten'. Ok tha'katierénhtsi, wa'katkáhtho' kahòn:tsi nikaieron'tò:ten' oniehtó:kon nontakaiakénstahkwe'. Wà:kehre' ska'niónhsa owí:ra nen' nè:'e áse' kenh tó:kenske' kaia'towá:nen' tánon eh onerahtó:kon' ioná:tkaron. Ohkwá:ri' kèn:ne.

Orihwí:io wakaterièn:tarahkwe' tsi iah tewákken' tánon iah tewatia'táswen áse' kenh tsi nonkwá:ti' wa'owerarátiene'. Iah tewakaterièn:tare' tóka' ok nahò:ten wa'otianerónhkwen' nek tsi ok tha'katierénhstsi tontáhsawen' takatákhe'. Ia'kanitskotákwahte' tánon wa'tewakhenrehtánion', kwah í:kehre' ia'tkaié:ri tsi niio'nikonhrá:tahkwe' aiotó:ken'se ka' nonkwá:ti nontonkwatewenninonhátie' tánon tontáhsawen' é:ren sá:wehte'. É:ren shonsaiawehtonhátie', tohkára na'tke'nhiahtià:khon' tánon ontè:ko'.

Sewatié:rens akonhà:'ak wa'kató:rate' tánon sha'karòn:tate' skaià:ta ska'niónhsa, tohkára nikarì:wake' wa'keweientéhta'ne tsi nátiere' nó:nen enkaròn:tate' ne kário'.

Ne niá:re' ne takenonhwerá:ton'. Tien'kwenhá:wi' tánon tekatenonhwerá;tons. Ietié:nas naóhwhare, skatathrewahtén:nis tánon katonhrahserón:nis.

Ok ne tekeníhaton tsi nitiéhrhane ne ki' ne akáhsete' tsi nikahi'kará:ke' iohi'karón:ton' nona'karà:ke.

Ok ne ahsénhaton tsi nitiéhrha ne ki' ne tohkára nakerastánion.

Ok ne ohna'kénhka tsi nitiéhrha ne ki' ne akaterien'tatshén:ri' tsi ní:tsi atià:tia'ke kí:ken' tó:k niwaní'ta.

Kahseriie'towá:nen khseriie'tenhá:wi tánon nó:nen enkaia'taién:ta'ne ne ska'niónhsa, enké:sake' skakwí:ra' aktóntie nonkwá:ti'. Kwah nè:'e ne kaia'takwe'ní:io ne ki' ne okwirà:ke ákhnerenke ne ohnà:ken aohsí:na' tánon akate'nién:ten' è:neken' nonkwá:ti' natié:ra'te ne aonekwèn:ta, sok thò:ne à:share' én:ka'te tsi entià:khon'.

Nó:nen eniekahrostatáhko', kaia'takonhkó:wa ia'tesanentshénhton' áse' kenh teiotonhontsóhon' enhsó'kwate' è:neken nentéhse' tánon enhstéhthare' ne entskwè:na óstien' ne ki' naón:ton' orihwakwé:kon' aktáhko'.

Tóka' ia'tetià:ti', enkkahrostatáhko' sok o'nèn:ra én:katste' tsi enke'rhó:roke'. Tsi iohahakwe'ní:io shos iénske' tóka'ni tsik nón:we ioiánere takeronwarahsónteren' tánon ienkheiatewennáta'se naiontié:nawa'se atia'torià:neron' áse' kenh kwah tokèn:'en iotiia'tákste' thí:ken ska'niónhsa.

Kwah se' ó:ni nó:nen akwé:kon enhsià:khon, shé:kn wentó:re'.

"Iontkéhtats à:there" ronnón:nis ne Ahkwesásne nonkwá:ti, iehsnonhsà:ke ióhson' ó:iente ionnià:ton à:there' nen' nè:'e néne wá:tons ahsatkéhtate' skátne ahsá:ra'.

Iotkà:te' nó:nen enhsià:khon ne ska'niónhsa, skarihwátshon' enhsatkéhtate' thí:ken kaià:khon.

Tho shos nenhatí:iere' é:so rá:ti ne thotí:iens, rotikéhte' ska'niónhsa ohsí:na' ne tho a'therakónhson watáhkhe'.

Shé:kon kwah tokèn:'en iókste' thí:ken aonhà:'ak ohsí:na tánon teiotonhontsóhon' tohkára nenhsáhkete'.

Sewatié:rens ensatera'swí:ioste' tánon sénha ohahákta' enkaia'taién:ta'ne ne ska'niónha ne ki' aón:ton' tohkára nika'seréhtake' énhsatste' nahskaré:ni ne ska'niónhsa. Nek tsi tóka' iah, tó:kenske' tsisakéhtátie.

Thóha teiohserá:ke nikaiá:nes ne skaià:tak ska'niónhsa o'wà:ron. Tánon tió:konte' nó:nen enke'wà:rake', orihwí:io enkón:ni ne takenonhwerá:ton'.

Edited by: Aaron McComber, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Translated by: Karonhí:io Delaronde